Hegemony

James Bridle defines artificial intelligence as a very limited way of conceiving intelligence: AI, he argues, is intelligence as designed by a corporation1.

This definition applies particularly well to AI-generated images, which come from a small number of companies, including OpenAI (ChatGPT), Anthropic (Claude), Google DeepMind (Gemini), Meta (LLaMA), Mistral AI (Mistral), DeepSeek, and Stable Diffusion.

Some of them — such as Adobe or Getty Images — also operate as stock image platforms. This is because both systems follow the same underlying logic: transforming creativity into a standardized, indexed, and exploitable flow, based on the massive capture of content. They thus participate in the same regime of image industrialization, in which value derives less from creation than from the algorithmic management of inventories.

The concentration of these actors establishes an iconographic hegemony, in which the same aesthetic, technical, and economic models circulate among AI systems, platforms, and image banks.

However, these companies do not merely flood the world with their images. They also deploy bots to scan the web for copyright infringements. We tend to focus on AI’s spectacular advances in generating striking images. Yet it is precisely these advances that make automated copyright enforcement possible. Copyright, let us recall, was not originally designed to remunerate artists, but to ensure the profitability of cultural production.2.

The shift from image generation to the automated surveillance of circulation shows that AI is not only a tool of production, but also a system of management. The same technology that promises infinite creativity also serves to lock down the conditions of access, use, and appropriation

Monoculture

The intense capitalization of stock image groups and AI companies evokes a form of monoculture. Scale-driven production favors robust, predictable visuals, calibrated for mass circulation rather than for surprise or disruption. What emerges is a monoculture of images — a homogenization of image-production processes that tends to reduce the diversity of creative practices to a set of gestures compatible with large generative models.

This monoculture profoundly shapes visual grammars, orienting what can be imagined, represented, or even perceived as plausible. In other words, the very conditions of possibility for imagination are being flattened.

To circumvent this system, one must develop technical capacities — whether by creating images through traditional means or by using open-source AI tools, which are necessarily less powerful when they lack access to the vast quantities of data accumulated in the vaults of cognitive capitalism.

The image world could come to resemble industrialized, globalized agriculture, which constantly reduces the diversity of consumable products — not to mention the ecological devastation it causes ☛ Junk. Diversity thus becomes economically disincentivized: in general, it is faster and cheaper to generate an image using the immense capacities of big data than to produce one oneself.

Powder

A phenomenon runs through social media, AI, and stock image platforms alike: an algorithmic logic of domestication that reduces images, individuals, and all cultural production to what can be turned into powder — that is, broken down into easily recognizable fragments, sorted and classified according to patterns, and then converted into exploitable data.

Media theorist Paul Frosh identified three major technological transformations that profoundly reshaped the stock image sector during the shift from analog to digital in the 1990s and 2000s.3 The first concerns the introduction of applications such as Photoshop, which made it possible to manipulate images with extreme precision. Photography thus definitively lost its status as a “natural” representation4 and came to be seen as an artificial construction. The second transformation is linked to the development of keyword indexing, which made it possible to organize ever-larger visual archives. This requires substantial resources and constant updating — a time-consuming task — but in a saturated market it guarantees traceability and relevance, and thus commercial value. The third transformation concerns digital distribution, first on CD-ROM and then via the web, which drastically reduced costs and expanded accessibility.

The process described by Frosh is part of a longer history, traced by Estelle Blaschke through the fate of the Bettmann Archive.5 Unlike most agencies and commercial photographic archives, which promoted their most iconic or sensational images, Otto Bettmann developed a system combining miniature photographic prints with detailed textual metadata. What was promoted was less the images themselves than structured excerpts from the index: a mapping of knowledge through the visual, privileging indexing itself as a form of value.

The history of image domestication thus runs through words. These are indexed — that is, transformed into data and metadata. The current practice of tokenization (breaking an entity into smaller elements, or tokens, to enable digital processing) is only the latest avatar of this process. Stock image platforms operate through logics of fragmentation and standardization: keyword classification, segmentation into meaningful units, and optimized distribution via search algorithms. These images are not only the result of visual learning but also of their inscription within an algorithmic regime of visibility inherited from the very functioning of stock image banks.

Stock images thus contributed to the fragmentation and datafication of images — a symptom of a more general datafication of the world and of our conception of it. 6

This practice of datafying text in order to associate it efficiently with an image, making it manageable and marketable, eventually extended to the images themselves. Mechanical, and later algorithmic, classification logics render them naturally compatible with today’s artificial intelligences. AI-generated images are patched — segmented into small visual blocks (patches) — or discretized into latent codes using predefined vocabularies (codebooks). Their semantic proximity is no longer based on intuitive resemblance but on relational structures that emerge statistically. Fragments become manipulable in multidimensional latent spaces, each of which can be brought into relation with others to recombine a vast number of new images. Here, AI merely amplifies a movement that began several decades ago.

What is at stake is the fabrication of a malleable matter, like animal feed meal or reinforced concrete.

One and the same mechanism underlies generated images, generated thought, generated music, and so on: reduction to powder.7 This process closely resembles the way social media occupy fragments of time — lost moments, waiting, pauses, and other crumbs of life that we do not fill with specific activities but which they seize and exploit so easily. Our time, too, is reduced to powder and reconfigured. We are then reorganized from within by these recomposed fragments. Addiction to these media imposes their time upon us ☛ Shortcut.

What these systems — and those who own them — seek is not the singularity of forms, but their capacity to be cut up, computed, and monetized.

Extraction

During their training phase, generators are trained on vast image corpora, including copyright-free content such as Wikipedia, Wikimedia Commons, Reddit8, and all kinds of stock imagery. Getty Images, The New York Times, and Le Monde have signed agreements with OpenAI. All of this data is then taken up and digested by equally automated mechanisms, which produce infinite variations. When we send a prompt, we certainly receive a response — but at the same time, we feed our data back into the reinforcement of AI systems.

These images are quick to devour everything. They devour the planet’s resources. They devour human culture.

There is something sacrificial in the way we offer our work as fodder to generative AI.

Blue

How do stock images envision their successors?

How do they represent the idea of artificial intelligence?

Stereotypes abound when it comes to visually representing AI: smooth white robots, 0s and 1s floating in space, or humanoid-robotic variations on Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam. These representations can be seen as paradigmatic: they reveal how stock images “see” and “show” the world. These smooth robots are not so different from the bright smiles of call center employees, or the empty, spotless streets of urban neighborhoods without inhabitants.

We have paid particular attention to the frequent presence of the color blue in these images.9 M. Although this type of representation has somewhat declined in AI-generated images, especially since the launch of ChatGPT10, it continues to play an important role and deserves further study. One only needs to ask ChatGPT — or any other multimodal AI — to generate an image with a simple prompt such as “Show me artificial intelligence.” The result is almost always the same: an image that follows all the conventions of stock imagery — the color blue, printed circuits, an androgynous profile, 0s and 1s. As we have argued elsewhere11, these images exert an anesthetizing effect on debates about AI and its impacts.

Moreover, how can one visually represent AI today, when stock images constitute one of the main “feeds” for generative AI? Trained on an immense quantity of these images, AI can only tend to reproduce their conventions, especially since alternative materials are virtually nonexistent. Stock images, because they form the aesthetic backbone of the initial datasets, continue to exert their influence. They are imitated, regurgitated, amplified — to the point of threatening the stylistic and conceptual diversity of the models themselves.

From this perspective, the most stereotypical stock images paradoxically have the merit of pointing to the invisible dimensions of AI: its imaginaries rather than its reality. They evoke fears and hopes. They do so endlessly, always in the same way — and it is striking how few themes they actually mobilize despite their profusion. AI stock images resemble sacred icons, which, as Pavel Florenski observed12, do not abandon perspective and realism out of ignorance, but by choice: the choice to leave a gap between the visible and the invisible.

There are certainly more daring images and artistic productions, but these remain marginal and tend to dissolve into the vast latent spaces of contemporary AI.

The question is therefore not which imaginaries, effects, and biases AI will produce in our understanding of AI, but rather which imaginaries, effects, and biases are already present — notably through stock images — and that AI merely reproduces. And, of course, what holds for AI also applies to many aspects of sociotechnical reality, and to social and cultural reality in general.

Autophagy

At the end of the image food chain sit generative AIs. They consume everything. They are trained on other image stocks, devour the stocks from which they originate, and then feed on their own outputs in a cycle of retro-ingestion that some researchers call AI autophagy, or Model Autophagy Disorder (MAD).13

The autophagy of images is also that of culture and of our relationship to the world. In a strange reprise of Saint Paul’s epistles, we count the remaining time before being devoured.14 We are still here, thinking we are safe — yet quite the opposite: we are being reduced to fragments, anticipating our engulfment in an apocalypse that has already begun.

As early as 2006, artists Paolo Cirio, Alessandro Ludovico, and Ubermorgen launched the project Google Will Eat Itself, which aimed, quite literally, to buy back Google by hijacking its appetite for advertising. Google text ads were placed across a network of hidden sites, and the revenue generated from these ads was then converted into Google shares. This attack, unfortunately, never went beyond the symbolic stage, but it opened up the possibility of exploiting an autophagic flaw in a hegemonic process.

Google, however, feeds primarily on external content. AI, by contrast, largely regurgitates its own “juice” ☛ Juice. This is its Achilles’ heel. Could this weakness be exploited?

Discovering an internal autophagy loop does not, of course, mean that AI will consume itself. Nonetheless, the film Everything is Real aims to give a visual form to this recursive process ☛ Apple Obsession).

Infiltration

We are infiltrated from all sides by AI. It enters through our attentional pores, stealthily slipping into the unoccupied corners of our lives without us having to send a single prompt. It smooths the results of our search engines, creates the content on the social media we browse, calculates our routes, optimizes our online orders, retouches faces in the photos we take, enhances our smiles…

We already knew that our bodies were made of stardust. Then we learned that our blood, hair, liver, and even our flesh were invaded by microplastic dust.15 Now we know that they also harbor dust from latent spaces. Fragment by stealthy fragment, these particles contaminate our vital organs — starting, of course, with our brains.

Genealogy

In 2022, we launched the scientific and artistic research project BIAS — Banques d’Images et Algorithmisation de la culture viSuelle.16 The name deliberately plays on the ambiguity of the word “bias”: the project started from biases in images (gender, race, class, etc.) but, above all, aimed to approach generative AI through one of its main training materials: stock images.

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, stock images suddenly became ubiquitous. With the spread of online platforms and the emergence of low-cost “microstock” portals such as Shutterstock, iStockPhoto, Dreamstime, Fotolia, and Bigstockphoto, catalogs grew to unprecedented proportions. Photographs, illustrations, 3D models, and videos were produced on an industrial scale and sold at rock-bottom prices. Their massive use made them omnipresent in our lives. They now cover our entire visual universe, decorating city walls, transport systems, screens, and media; feeding films of all kinds, TV documentaries, advertisements, magazines, corporate annual reports, clickbait articles, food packaging, high-tech product packaging, emails, memes, personalized greeting cards, construction tarps, and even the sides of rental cars…

By 2025, the market leader Shutterstock offers over a billion media items, including more than 450 million images, as well as countless videos, illustrations, and audio tracks. These staggering numbers are made possible by the same platform-based system that underlies the success of Uber, Airbnb, or Deliveroo, and that generalizes gig-based work — or “taskification.”

Stock images occupy a central place in the training corpora of contemporary AI. AI has absorbed not only their standardized aesthetics but also the ways in which platforms created, classified, and distributed their products.

What we now call “artificial intelligence” is only the tip of a much deeper historical iceberg. It is impossible to understand the production of images by generative AI without reconstructing the history of the domestication and segmentation of the visual.

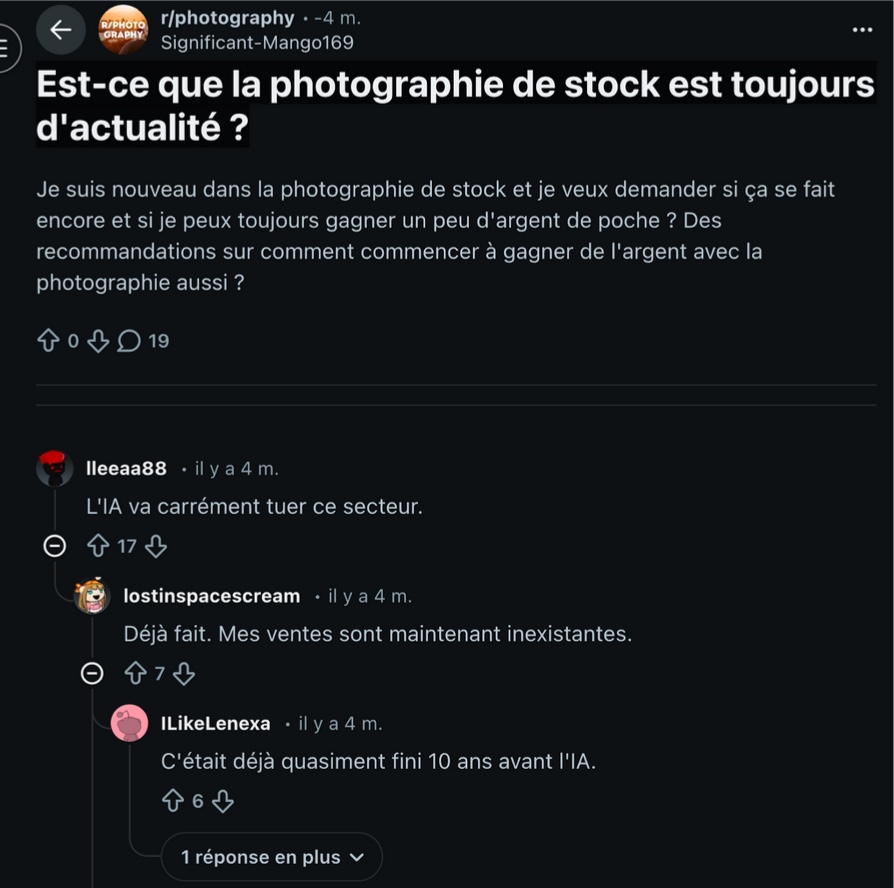

Ironically, in just a few years, stock images have found themselves supplanted by AIs that have consumed them so intensively that they are now making them disappear. The image eats itself.

Smoothness

AI-generated images inherit from stock photography their characteristic smoothness. Everything must glide effortlessly.

These images are not meant to create friction; they should not disturb, shock, or provoke — at most, they can nudge certain emotions or reactions. They are designed to charm without resistance, to influence without tension. This perfect legibility, this apparent neutrality, constitutes an aesthetics of fluidity that is also an ontology of the surface: everything is visible, but nothing is thought. Smoothness should be understood here both as an aesthetic operator and as a political device: it neutralizes dissent, flattens affect, and prevents critical thought from arising. It is within this texture without grain that the autophagic logic of automated generation takes root — a smooth repetition of smooth forms.

Perhaps the most intriguing aspect of this peculiar visual genre — stock images — is that no one pays attention to it. Every day, we see dozens of them, whether on billboards, websites, university brochures, magazines, corporate reports, and so on. Yet we never stop to look at them. They leave no imprint on our consciousness and immediately fade into the background. They constitute the “wallpaper” of our consumer culture.17 The invisibility of these images is, in a sense, intentional: by definition, they must remain generic. They are made to go unnoticed. 18

Researchers themselves are not exempt from this invisibility, and may even be guilty of a certain intellectual snobbery that leads them to privilege the “noble” forms of our media and cultural productions. Nevertheless, a small number have focused on these images, particularly to denounce the biases they convey.19 A sub-group of this research has examined the role stock images play in shaping our imaginaries of emerging technologies, especially artificial intelligence.20

Generative AI productions — aside from their infamous “hallucinations” — also tend to be generic, as indistinct as stock images. They impress by their ability to imitate real images.

As for text-generating AI, its stroke of genius lies in disguising itself as an intimate, informal conversation.21 The ChatGPT interface is deliberately welcoming and friendly, making the generation experience familiar. One can chat with it and receive responses that are always polite, empathetic, sometimes sprinkled with lightness or irony. There is no denying that these texts “work”: they are structured, grammatically flawless, informative, often correct, and presented with an elegant appearance.

Everything must glide effortlessly. In this respect, generated images and texts resemble background music. Here is how this particular musical genre was described by Umberto V. Muscio, known as “Bing,” who ran Muzak, the US market leader, in the 1970s:

All forms of art require intellectual or emotional participation, thus participation of consciousness. That is exactly the opposite of what we do. We play background music that sets the mood of the environment. We play it so that you hear it, but without listening. 22

Background music, too, obeys the rules of composition, relentlessly seeks harmony, and follows every rule. Devoid of notable accidents, roughness, or intrusion, it is characterized by its lack of surprise. Achieving this requires highly skilled professional musicians or, more recently, AI. But it follows the rules to the letter, never exceeding them. Background music meets our expectations exactly — something that “music” (music meant to be listened to) does not.

These texts, music, and images “flow naturally.” It is precisely their formal perfection that renders them flat, devoid of the singularity that gives embodied writing, music, or imagery its strength. They are perfect for press releases or to fill time in a waiting room, but may be inadequate for in-depth analysis, evoking thought, eliciting emotion, raising doubts, or provoking debate.

The paradox is that, despite their invisibility, stock images exert a powerful influence on how we interpret and understand the world around us. If generative AI encourages conformity and repetition, the real challenge is to use it differently, to create spaces for agonism. The concept of agonism, developed by political philosopher Chantal Mouffe, envisions conflict as a constitutive element of democracy, opposed to a consensual view of politics.23 For Mouffe, societies are crossed by irreducible divergences and deep disagreements, which should not be eliminated but rather channeled constructively. What we propose, in sum, is a use of generative AI aimed at provoking forms of agonism in our societies.

In a similar vein, Marcello Vitali-Rosati recently proposed Éloge du bug (In Praise of the Bug) (2024) as an invitation to distance oneself from the seemingly perfect functionality of contemporary digital technologies. For Vitali-Rosati, the bug is far more than a failure: it becomes a material metaphor for a critical practice of distancing oneself from the pursuit of fluidity, frictionless efficiency, and the absence of conflict with the user. This immediacy and ease of use — found in tools like ChatGPT — result from design aimed at minimizing any need for exploration or deep engagement. Éloge du bug thus becomes a call to create resistance and friction: for example, preferring an open system like Linux over closed environments, or tinkering with one’s own machine, even at the cost of its imperfections. This approach requires time and resources but constitutes a valuable form of autonomy in the face of technological standardization.

By pushing AI to pull, divert, and derail the stock images and videos that structure it from within, we seek to explore the machine’s internal latent spaces — its potentialities, biases, and limits — as well as the extra-machinic, cultural latent spaces that have sedimented in these generic images over time.

Junk

In their book L’IA, junk food de la pensée (AI, the Junk Food of Thought), Christophe Cailleaux and Amélie Hart compare the rise of generative AI platforms to the emergence of junk food: ultra-processed, cheap, mass-promoted by the food industry, and responsible for numerous health problems. Junk food makes eating as easy as producing it, bypassing natural digestive processes. Generative AI platforms are similarly designed to produce quickly whatever is requested of them, creating perfect hamburgers, pizzas, donuts, and chips — shiny, greasy, sweet images.

Now imagine that, in addition to the harmful effects of junk food (increased cardiovascular disease, diabetes, obesity, cancer, allergies, degenerative diseases, infertility, etc.), we add the consequences of widespread generative AI use, with all the disorders it would produce: information overload, overconsumption, attention disorders, informational obesity, pollution, cheap aesthetics, filler content, hyper-normalization of ways of seeing, stereotypes, simplification, hyper-categorization, neutralization, and so on.

Obsession

We did not want to remain outside AI, nor to confront it head-on. We chose another path: to dive inside, follow its own logic, until it exhausts itself or turns against itself. We immerse ourselves in the very material of generative AI images and navigate within them, adopting a participant-observer stance.

In the 1970s, British architect Reyner Banham, seeking to understand Los Angeles, wrote: “Like previous generations of English intellectuals who learned Italian to read Dante in the original, I learned to drive to read Los Angeles in the text.”

We push AI to its limits, to the saturation of its stereotypes. The film Everything is Real24 stages automation, repetition, and algorithmic amplification. We draw on the archaeology of stock images to turn generative AI back on its own sources and its own biases, mining the layers of its stereotypes, implicit narratives, and frozen imaginaries.

We had already assembled a corpus of the most widespread stock image tropes.25 We then recreated each of these images using the most common generators. Everything is Real thus shows the reddest apples, the greenest call centers, the most wired server rooms, the most efficient volunteers, and the largest mountains of waste. But by looping these stereotypes, the images gradually tip into the extreme. The red apple, alone on a white background, appears in the hands of employees who smile a little too much, then gorge themselves until they sink into their own juice ☛ Juice.

The goal is certainly not to stop the machine (we would be incapable of that), but perhaps to reveal its contours. We did not fully enter the latent spaces either. But we could sense them, always going with the current, paying close attention to what the prompts returned until they themselves reached saturation. It is a way of exposing the machine’s belly.

Employees, carried away by their sales celebration sessions, throw banknotes into the air, before being buried under a rain of money.

Call center operators work in environments as green as possible, until they fall in love with the proliferating plants.

Volunteers clean pollution from toxic sites until even the sand on the beaches turns green. The Earth becomes an object held in the hand, protected and cherished, only to be discarded on a mountain of waste.

Protesters hold up empty signs in various locations, then the world around their struggle gradually disappears. The signs demand a return to reality: I am real, We are real, We are in reality, Everything is real.

Juice

Generative AI images blend into a sticky juice. They clump together all existing materials. This juice flows to illustrate the entirety of the visible world: advertisements, promotions, sales, announcements, illustrations, articles, newspapers, reports, information, books… Everything dissolves into a smooth, neutral, corporate imagery designed to be seen only by robots and machines, which in turn feed on it to generate other ads, other reports, other articles.

This generates a form of gluttony26 and saturation, oscillating between insatiable desire and nausea in the face of excess — two sensations feeding each other, like two moments of the same appetite.

Now imagine this mechanical juice escaping from our mouths. It literally flows from our lips. It spreads like grey goo, the gray matter of computation. The juice flows continuously. It floods. It drenches us until we are drowned in an ocean of images ☛ Obsession.

Shortcut

“AI frees us from thinking: it does it for us so we no longer have to. […] Since no activity can truly be delegated (enjoying by proxy is hard), not even life itself, there has to be a fundamental misunderstanding of the meaning of praxis to believe one can enjoy its fruits while being freed from its conditions of possibility.”

Sébastien Charbonnier27

In a just-in-time society where everything tends toward maximum productivity, companies are constantly offering new shortcuts, without caring if things move too fast, and without concern for the breaking point inevitably reached by acceleration. Waze finds the fastest route instantly. Amazon delivers in under 24 hours — or even before you’ve ordered. Uber connects you immediately with the nearest driver. Social media offers shortcuts to your friends. Information bubbles confirm what you already think, saving the effort of contradiction. Tinder provides instant possibilities for meeting new people. Binge-watching accelerates entertainment. Binge drinking puts you in an altered state immediately.

This speed is the very principle of generative AI. It offers a shortcut to the acceleration — even the zapping — of thought-making. Constantly relying on the formulas calculated by these machines gradually replaces visuals with ready-made images. The short-circuiting happens in stages, almost imperceptibly.

We know the trap of the shortcut, and its outcome: “The short-circuit […] is a pure and simple negation of what learning essentially is: paths, processes, made of understanding, design, awareness, and procedural realization”.28 Daniel Schacter, Harvard psychology professor, explains this in reference to Jorge Luis Borges’ story Funes, or the Memory:

"A young man remembers every detail of everything that happens to him. He remembers every leaf of every tree he has seen and every occasion on which he saw it […] But the price of perfect retention is high: Funes’ mind is so clogged with precise memories that he is unable to generalize from one experience to another. He struggles to understand why a dog bears the same name the first time he meets it and a minute later. Borges reminds us that ‘to think is to forget a difference, to achieve abstraction.’ […] Years after Borges wrote this story, Russian neuropsychologist Alexander Luria described a subject with prodigious memory […] He could recall long lists of names, numbers, and anything else without error […] This was useful in his work as a reporter, as he didn’t need to write anything down. However, when reading a story or listening to others, he recalled endless details without truly understanding what he had read or heard. And like Funes, he had great difficulty grasping abstract concepts."29

Today, we are in Funes’ position, engulfed by infinite knowledge, unsure what to do with it, as it overwhelms our mental capacity to hierarchize information. Nothing prepares us to handle such an amount of data. No effort separates us from knowledge. Nothing remains obscure.

Of course, this knowledge does not crowd our brains: it is stored on servers far from our physical bodies. But it makes no difference if we have immediate, constant access. Even on the other side of the world, it is still a shortcut. And the danger of a shortcut is arriving too quickly at the destination. If the answer to any question is instantly accessible, there is no need to search for it ourselves, and thus no need to think. Speculative thought loses its purpose. Wandering, deviating, embarking on a long pilgrimage, or getting lost can prove more productive. The effort to find one’s way generates intellectual output. What emerges is not pure knowledge: it is human creation, even if inaccurate, improbable, or absurd.

Those who lack the strength to resist the sirens of omniscience will be unable to leave any detail unknown; they will no longer know how to generalize an idea. Gradually emptied of their intellectual capacities, they will become mere access points to knowledge — in computing terms, peripherals of the planetary brain we have created.30

Apple

"In the seventeenth century, seventy apple varieties were recognized by Pierre Le Lectier. […] On the eve of the Revolution, the catalogue of the Carthusians of Paris counted only forty-two varieties. […] By 1960, only one French apple was classified as Grade I and could enter the modern distribution circuit (convenience stores, supermarkets, hypermarkets, and other retail giants…). The other varieties (11,000 worldwide) could only be cultivated occasionally by a few small producers, who gradually disappeared under economic pressure. Biodiversity seemed severely threatened."

« Histoire de la pomme », Wikipedia FR, accessed November 10, 2025.

“If you are going to photograph an apple for stock, then strive to shoot the quintessential apple, the personification of applehood, the crispest, healthiest apple the world has ever seen. Anyone can drop an apple on a white background and shoot it, so your job is to rise above the rest and create an image that takes appleness to a new level. […] The angle at which it is shot makes the fruit look as if it is standing tall and ready for duty. The bright green leaf jutting off the stem speaks of freshness, as if it had just been plucked from the tree. The skin is free of blemishes, and the reflection of light on the top makes it shine. […] Take that same apple […] and put it in the hand of a lovely young woman lying in the dappled sunlight of a late summer day, and you can […] communicate a message of health or happiness […].”

Rob Sylvan, Taking Stock: Make Money in Microstock Creating Photos that Sell, Peachpit Press, 2008.

1James Bridle, Ways of Being: Animals, Plants, Machines: The Search for a Planetary Intelligence, Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2022

2See Antoine Defoort’s lecture Un faible degré d’originalité (L’Amicale de production), and the exhibition Image Capital by Estelle Blaschke and Armin Linke, presented between 2023 and 2024 at the Museum Folkwang in Essen, MAST in Bologna, the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation in Eschborn, Germany, and the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

3Paul Frosh, The image factory: Consumer culture, photography, and the visual content industry. Berg, 2003.

4This status of naturalness never truly existed. Since the nineteenth century, photographs have been retouched and manipulated, whether through spirit photography, the beautification of faces in portraits, or the brushing out of figures deemed undesirable from political images.

5Founded between Berlin and New York, the Bettmann Archive was acquired in 1995 by Corbis, an image-licensing company created by Bill Gates, whose ambition was to build a vast visual encyclopedia. The goal was not to accumulate as many images as possible in each category, but rather to multiply categories, in an explicitly encyclopedic project. Over time, the indexing system was rationalized to improve commercial efficiency.

6Alberto Romele, “The datafication of the worldview”, AI & Society, 38, 2023, p. 2197–2206.

7Voir le film Cyborg in the Mist (Stéphane Degoutin and Gwenola Wagon 2011) https://d-w.fr/en/projects/cyborgs-dans-la-brume/.

8Wikipedia and Reddit are the main sources used by generative AI tools in the United States.

9Alberto Romele and Dario Rodighiero, “Nel blu dipinto di blu; or the “anaesthetics” of stock images of AI”, blog.betterimagesofai.org, December 2, 2021. (2)

10Pablo Sanguinetti and Bela Palomo, “Bridging gaps in AI representation: A cross-cultural analysis of media imagery”. Journalism Practice, 2025, pp. 1–21.

11Alberto Romele, Images of artificial intelligence: A blind spot in AI ethics. Philosophy and Technology, 35, 2022.

12Pavel A. Florenski, La perspective inversée, Allia, 2013.

13A list of references on this topic is available at https://dsp.rice.edu/ai-loops/. Accessed September 4, 2025.

14Giorgio Agamben, Le temps qui passe, Payot & Rivages, 2017.

15Pierre Cassou-Noguès et Gwenola Wagon, Les images pyromanes, UV, 2025

16The BIAS project was developed between 2023 and 2024 by Stéphane Degoutin, Alberto Romele, Antonio Somaini, and Gwenola Wagon, with the support of Sorbonne Alliance. It was structured around a traveling seminar dedicated to the uses, imaginaries, and technical logics of stock images. One session, for example, focused on representations of artificial intelligence — both those produced by stock image platforms and those generated by AI — in a highly symbolic location: the Chapelle de l’Humanité in Paris, designed by Auguste Comte. The project unfolded at a pivotal moment, marked by the accelerated transition from stock images to generative images. This shift was accompanied, if not precipitated, by a reconfiguration of the market itself: after signing agreements with AI companies such as Nvidia and OpenAI, the two main global agencies, Getty Images and Shutterstock, merged in January 2025.

17Giorgia Aiello, “Taking stock. Ethnography Matters”, 2016. https://ethnographymatters.net/blog/2016/04/28/taking-stock/. Consulté le 4 septembre 2025.

18Stéphane Degoutin and Gwenola Wagon, “Le blanchiment des images” (Image-washing), AOC, 6 avril 2022. https://d-w.fr/fr/projects/culte-du-stock/

19See, for example, Crispin Turlow, Giorgia Aiello, and Lara Portmann, “Visualizing teens and technology: A social semiotic analysis of stock photography and news media imagery,” New Media and Society, September 19, 2019; Giorgia Aiello and Anna Woodhouse, “When corporations come to define the visual politics of gender: The case of Getty Images,” Journal of Language and Politics, 15(3), 2016, pp. 352–368.

20See, for example, Stephen Cave and Kanta Dihal, “The whiteness of AI,” Philosophy and Technology, 33 (2020), pp. 685–703; Beth Singler, “The AI creation meme: A case study of the new visibility of religion in artificial intelligence discourse,” Religions, 11(5), 2020, pp. 1–17; Alberto Romele and Marta Severo, “What do AI images want? An exploration of the visual scientific communication of artificial intelligence,” Sociétés et Représentations, 2023/1(n° 55), pp. 179–201.

21See, for example, Carl T. Bergstrom and Jevin D. West, https://thebullshitmachines.com/. Accessed September 4, 2025; “In a marketing masterstroke, AI companies presented our interaction with LLMs not as an autocomplete function but as a chat window… This small change makes a huge difference in how we interact with these machines and what we expect from them.”

22Pierre-Pascal Rossi (journalist) and André Gazut (director), Une si douce musique (Such sweet music), documentary film, RTS (Radio Télévision Suisse), 1978. Visible at this address: https://www.rts.ch/play/tv/temps-present/video/une-si-douce-musique?urn=urn:rts:video:9461786. Accessed september 4, 2025.

23Chantal Mouffe, Agonistique : Penser politiquement le monde, Beaux-Arts de Paris éditions, 2013.

24https://d-w.fr/fr/projects/everything-is-real/. Accessed September 4, 2025.

25For a film presented in the exhibition Le culte du nuage at Galerie Les Limbes, Saint-Étienne, 2022. https://leslimbes.com/expositions/2022/2022/le-culte-du-nuage/. Accessed September 4, 2025.

26On the devouring of resources (water, minerals, rare earths, but also labor, personal data, etc.) — see also Kate Crawford, Atlas of AI: Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence, Zulma, 2022.

27Sébastien Charbonnier, “Refuser de parvenir à surproduire des merdes inutiles avec l’IA”, lundimatin, 17 octobre 2025.

28 Christophe Cailleaux and Amélie Hart, “L’IA, junk food de la pensée”. Academia, accessed March 1, 2025. https://doi.org/10.58079/13e71

29Daniel Schacter, Searching for Memory: The Past, the Mind, and the Brain.

30Adapted from Stéphane Degoutin, “Les sirènes de l’omniscience,” (The sirens of omniscience) Nogoland, 2010, , 2010 https://www.nogoland.com/wordpress/2010/01/les-sirenes-de-lomniscience/